by Carolyn Edlund

A conversation with bestselling author and artist Nick Bantock about art, the creative process, and writing his 27th book.

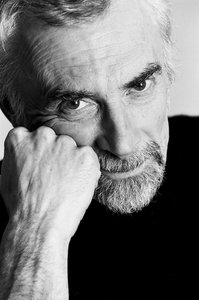

Nick Bantock

Photo: Yukio Onley

AS: Tell us about the new book you have just released.

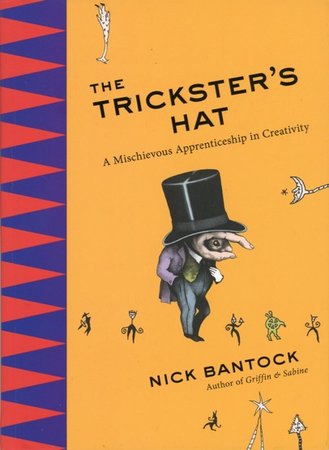

NB: The title is The Trickster’s Hat, and the subtitle is “A Mischievous Apprenticeship in Creativity”. What I concentrate on is partly the relationship between words and images, but mostly it’s to help people dig a little deeper to hit the core of their creative juices.

So much art that you see, and even much writing, tends to skate across the surface, mostly because people fear actually going into themselves and facing the things that really matter to them.

AS: Would you say that your workshops and your book are geared for writers, artists, or both?

NB: I tried to make it as available as possible to anyone who wants to expand their creativity and get to know themselves better. It’s for artists or writers or musicians or anyone who feels either “stuck” and wants to move on, or wants to go deeper into their psyches to understand their relationship with the creative process.

Essentially in the book there is a lead-in of about twelve pages in which I talk in a “trickster-y” and provocative way, and then it goes into 49 exercises. The exercises vary massively from collage to writing and much more – it really is incredibly broad. But it’s all really geared to the same thing, trying to help people use both sides of their brain equally, so that they use intuition and logic in a true marriage.

AS: If a visual artist were to read the book or take one of your workshops . . .

NB: You would still get to do the written work. And through the years, I’ve often found the artists enjoy the writing exercises most, and the writers tend to enjoy the visual.

It’s one of those arenas of play (and you can’t be really creative without play) where you can start encouraging people to relax and let go of their predetermined assumptions about things. Then what they produce tends to be infinitely freer.

If you can help people to get their ego out of the way and see themselves more as a culvert or a pipe through which creativity passes, instead of seeing themselves as someone who is in control and defining, it becomes so much more of a rich process. People enjoy it more, the quality of the work increases.

In other words, you learn your skills. You are still putting in your 10,000 hours as Malcolm Gladwell says, but as time goes by, you let go of this notion that you know what something is going to look like before you start. That seems to me one of those things that is so incorrectly taught in school, that you should come up with an idea and then try to visually create it. My experience is you grow it in front of you, as a process. And the more you trust that process, the more extraordinary it is.

AS: I’ve noticed that you literally include words in your own artwork quite often. Can you talk about that?

NB: I think one of the things you have to be quite careful of is that language tends to supersede imagery in our culture. In other words, we look for the words to tell us what something is about. I tend to avoid putting anything in that is any way directive. The use of words that I include within my imagery is usually done in a semi-abstract way. It doesn’t do any harm to have language support imagery, but if it pre-informs, then I think it tends to make the visual world subservient.

“Ponte Sul”, acrylic & collage, 3.5″ x 4.5″ by Nick Bantock

AS: Do you feel the same way about the titles of your artwork?

NB: Yes, titling for me is back to the Trickster and the mischief. If you can create a title that is mischievous, and that tickles people’s fancy, use that to draw them in. In all of my work, what I am trying to do is encourage and support people to come up with their own questions. I’m not concerned about giving answers. I’m concerned about provoking curiosity.

AS: What is different in this new book from what you have created in the past?

NB: This one is very direct in terms of the teaching process. There are many step-by-step “how to” books out there. When I teach a workshop, I tell people, “Over the next few days, my idea is not to teach you how to make mini-Nick Bantocks, my idea is to try and give you the food to feed yourself for the next six months or a year in your own studio, so that you produce your own work, not replicate somebody else.”

Hopefully what these exercises will do is show various ways of working. For example, I introduced some of the techniques the Surrealists and the Dadaists used back in the twentieth century to break down language, like transferring a series of nouns from one article to another article so you get a written piece that is completely and utterly unexpected. And then using that as a starting point to write a story.

They are all devices and means to get people off their standard tracks of working and responding. The moment you jump tracks and you start to work in a different way, suddenly your work takes on a huge degree of freshness.

AS: Are you planning more workshops?

NB: No, quite the opposite. I can reach a lot more people with the book … it’s not the same as being in a workshop, but it does sow the seed.

This is partly because I am really pushing back to doing my own books. I took seven years off since my last book, when I was just concentrating on my teaching and my art. Now that I am back to writing books, I am really enjoying it.

When I first started writing books over twenty years ago, I decided I was going to write 50 books in my life. And I’ve actually done 27 to this point; I’ve got 23 more to go, and I’ve actually got titles for all of them. So if over the next ten to fifteen years I can get up to 50, then I can pop my clogs in content.

See the breadth of Nick Bantock’s work by visiting his Facebook page, where he posts images daily accompanied by very short stories, social commentary and more.

So excited about this! Just ordered the book. Big fan of Nick’s writing and art. The Griffin & Sabine trilogy is a favorite in the Griffin household.