by Carolyn Edlund

A conversation with artist advocate and business strategy consultant Elizabeth Hulings on the inevitability of rejection, strategies to cope, and how to move forward.

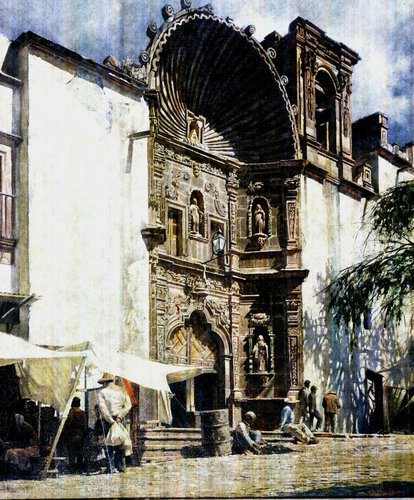

“San Miguel Cathedral” by Clark Hulings, oil on canvas

AS: It can be difficult for some artists to take an active part in selling their work because they fear the risk of rejection. How can a change in mindset overcome this roadblock?

EH: Artists of all stripes must figure out how to work through rejection. Of course, so do the rest of us. Whenever I work with solopreneurs, be they artists or chiropractors, I recommend establishing an entity (sometimes officially, sometimes just mentally) for the work. I have done that for myself with my consulting practice. I am a partner in the strategic advisory firm that I founded, named Counterpoise.

Carolyn, I know that your business is Artsy Shark. Whether you actually designate a name, or just go by Stephanie Sculptor or Peter Painter, separating yourself and the work you do is essential. It enables you to maintain perspective when criticism or rejection comes your way. That may seem like a small point, but it can really make a huge difference to be able to say, “OK, my business just got a bad review,” as opposed to, “That reviewer hates me and what I’m trying to say or do.” I did a whole talk about this recently. It was entitled “You are not your business.” Artists should use that as a mantra. They could also say “I am not only my practice.” Both work.

AS: Your father Clark Hulings was a very successful artist, which meant that he was also rejected from time to time. What lessons did you learn from his experience and his example?

EH: My father started out painting society portraits in Baton Rouge, LA, after WWII. As any portraitist will tell you, the work can be tough. He had many stories. One family loved the painting he did of their debutante daughter, except that, while she was sitting for him in her purple gown, they repainted their salon. So their interior designer made him change the color of the gown so that it would “harmonize.” The biggest problem with portraits is that, if the client rejects it, who else will want it? You have to have a certain temperament to be a painter whose subjects are able to voice their opinions. My father chose to paint other kinds of subject matter.

He moved from portraits to commercial illustration, and told me that breaking into that business at its apex (the 1950’s) was very difficult. He would drag his portfolio from art director to art director, leave it with the receptionist, and return later the same day to retrieve it, hoping they would want to hire him. Finally, he reached a point where he would slip a string in between two of the pages, just to know if anyone had bothered to look inside. In the end, he got hired to do newspaper wash ads and worked his way up from there, but it was rough.

Where I see a debilitating lack of self-esteem is not in their artistic practices, but rather in the business activities that are necessary to make them self-sustaining.

Eventually, my father made the move to easel painting, which is what he always wanted to do. He brought a few of his paintings to a gallery in New York and was told they wouldn’t take him on because he painted donkeys and laundry and churches and Mexico, and no one wanted those subjects. While the gallery director was explaining this to him, a woman came in and told the receptionist she wanted to buy the Mexican cathedral painting my father had brought in that was on the floor, leaning against the front desk. The director took him on so that he could get the commission.

I glean two valuable nuggets from these two stories: 1) Find the right niche for yourself. If you love the open air, go out and paint it. If you have allergies, don’t do that. This is important is because you will need to persevere no matter what, and if you heart isn’t in it, you won’t continue. 2) Always remember that the other party wants something, too.

AS: As the Director of the Clark Hulings Fund for Visual Artists who takes an active part in its business accelerator program, how have you seen artists gain confidence in dealing with rejection? What do you think are catalysts for this change?

EH: Confidence is definitely the right word. Most artists I know are very solid about what they want to create. Of course this can be shaken by disparaging words from a luminary, or repeated rejection by gallerists, critics, etc. But where I see a debilitating lack of self-esteem is not in their artistic practices, but rather in the business activities that are necessary to make them self-sustaining. For example, I often hear things like “I don’t even ask for contracts anymore, because they won’t give me one.” Well, the only thing you can be sure of is that if you don’t ask, you won’t get. I hear similar things with regard to pricing, marketing, and sales. For example, many artists don’t request the name and contact information of the people who purchase their work from third parties. In today’s market, this is just not OK.

So I feel strongly that there are three ways in which artists can inoculate themselves against rejection and the fallout from it: 1) Separate yourself from your product. 2) Do what turns you on. Don’t be belligerent about it, but don’t just follow the money, because you’ll burn out if you do. 3) Learn enough about the business side of things to feel comfortable having those conversations, so that you know what’s right and you’re asking for what’s fair. You may be rejected, but you won’t be exploited, and eventually you will get where you need to go.

Elizabeth Hulings is the director of the Clark Hulings Fund for Visual Artists, and a principal of the business-strategy consulting firm Counterpoise, where she has worked with startups, nonprofits large and small, multi-national corporations, and sole proprietors – including artists of many stripes. Before launching Counterpoise in 2001, Elizabeth worked on (and lived through) five Fortune-500 mergers at the predecessors of Citigroup, Cendant, and Verizon Communications. She also honed her skills at several nonprofit organizations, including the International Development Exchange, The Management Center/Opportunity Knocks, and Human Rights Watch.

Elizabeth Hulings is the director of the Clark Hulings Fund for Visual Artists, and a principal of the business-strategy consulting firm Counterpoise, where she has worked with startups, nonprofits large and small, multi-national corporations, and sole proprietors – including artists of many stripes. Before launching Counterpoise in 2001, Elizabeth worked on (and lived through) five Fortune-500 mergers at the predecessors of Citigroup, Cendant, and Verizon Communications. She also honed her skills at several nonprofit organizations, including the International Development Exchange, The Management Center/Opportunity Knocks, and Human Rights Watch.

Very sound advice.